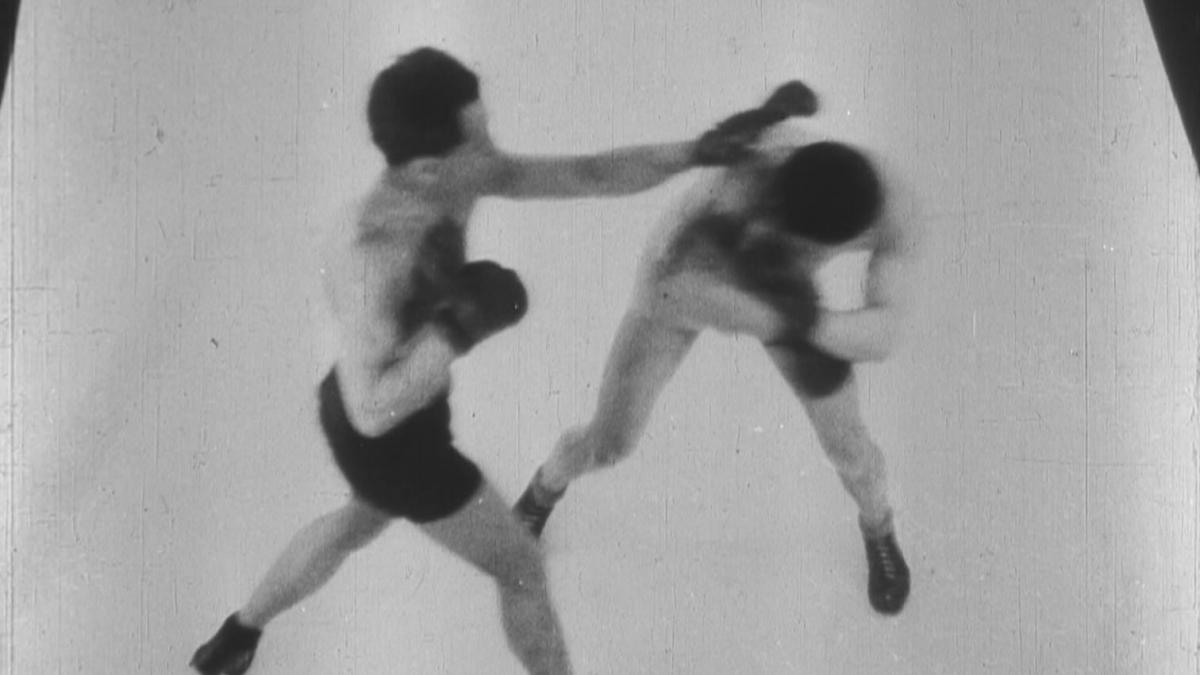

When Charles Dekeukeleire makes Combat de boxe, he is 22 years old and obsessed with cinema. He admires Vertov and his conception of the “camera-eye”. Paul Werrie, whose poem served as the basis for this film and who participated in the shooting, has described the precarious and improvised conditions of production. “A painter’s workshop was used as a studio … a few of us stretched out the bed-sheets which served as a ring. But the boxers were real boxers. They boxed on the sheets in front of a rope that two of us held up. Then, using an optical effect during editing, the film-maker combined the ring with authentic shots. They were just a blur of action. As for the crowd the fighters passed through, that was filmed in a school playground from the back of a milk float. Twelve of us were playing the crowd, standing in a line. When the camera had gone past, we left the back and ran around to the front, each time changing our hat and adopting a new pose, all of which created a very natural movement.”

This short, magnificent film is based on a high-speed montage, close-ups, superimpositions, the successive use of the negative and positive image and the principle of rhythm. The violence of the fight, the presence of the audience, the tension between the crowd and the ring are swept up in a dazzling choreographic montage, this succession itself transcended by the perfectly concrete shots which record less the abstract than the very meaning and the signs of the fight, the very concept of boxing.

“Dekeukeleire’s career seems to define the outer limits to which a filmmaker could go in the silent period with virtually no support. After four experimental films, it proved impossible for him to continue filmmaking in the same isolated way. To a certain extent we can say that Dekeukeleire was born before his time—not in the usual sense that audiences were not yet prepared to understand his films (although this is true—I think audiences accustomed to Snow, Conrad, and structural filmmaking probably have a better preparation for Dekeukeleire’s work than his contemporaries did). Rather, the filmmaking establishment was not set up in ways which could accommodate people like him.”

Kristin Thompson